Chinese Whispers, English Echoes, Korean Ghosts

Meekyoung Shin, exh cat., Korean Cultural Centre, London, 2013

I

The grand façade of 6 Burlington Gardens features an array of statues of great luminaries from the Western canon, including philosophers, poets, scientists and mathematicians. Milton, Newton, Plato, Gallileo, Goethe and Sir Francis Bacon all look down into the busy streets of London’s Mayfair. And the building thus declares its original purpose as a seat of learning, of innovation, of cultural endeavor and excellence.

This example of ‘a refined or enriched style of Palladian or Italian architecture' was designed in 1866–7 by James Pennethorne, to house London University. It was opened by Queen Victoria in May 1870. The University occupied the building until 1902 and it was then used by the Civil Service Commission until the 1960s. In 1970 the British Museum’s Department of Ethnography relocated to the building due to the lack of space in the museum’s main building in Great Russell Street. 6 Burlington Gardens was renamed the Museum of Mankind and remained so until 1997. During this period, alongside permanent and semi-permanent displays of objects from the extensive collections exploring specific societies, taxonomy and material culture, a series of innovative exhibitions occupied the galleries, including Japanese Shadow Puppets (1970), The Versatile Calabash (1981), African Pipes and Paraphernalia (1983), The Skeleton at the Feast: The Day of the Dead in Mexico (1992), as well as Eduardo Paolozzi’s ground-breaking cross disciplinary show, Lost Magic Kingdoms and Six Paper Moons from Nahuatl (1985-7).

The overriding characteristic of the displays was that objects that had been created in order to fulfill pragmatic roles within various societies around the world were presented out of context – or almost completely out of context – as artefacts to be mined for cultural, anthropological, taxonomic and ethnographic significance. Interestingly, given the Museum of Mankind’s proximity to both the Royal Academy and the many galleries on Cork Street, it became a rich source of inspiration for artists living and working in the capital.

In 2009, after a period of standing empty, 6 Burlington Gardens was occupied by the contemporary art gallery Haunch of Venison. In spring 2011 the Korean artist Meekyoung Shin presented a major exhibition that occupied the eastern suite of galleries and the state rooms. It was her largest exhibition to date.

This brief history of the building and its various guises, all presided over by the unchanging pantheon of learned and inspirational figures on the façade, suggests something of the loaded context into which Meekyoung Shin placed her work. In a sense, the building’s history of shifting cultural agendas provided a perfect platform for her ongoing exploration of identity, material culture and cultural meaning.

II

Entering Burlington Gardens, one approaches the exhibition rooms via a grand stone staircase. In April 2011 a central niche above the stairs – which was originally intended to hold a statue of Shakespeare – was occupied by what appeared to be a fragment of antique sculpture, a draped marble figure with a painted face. However, this was not a piece of antiquity but Translation – Greek (1998) by Meekyoung Shin. Here it provided the first intimation of the extensive exploration of shifting and slipping realities Shin’s exhibition would enact.

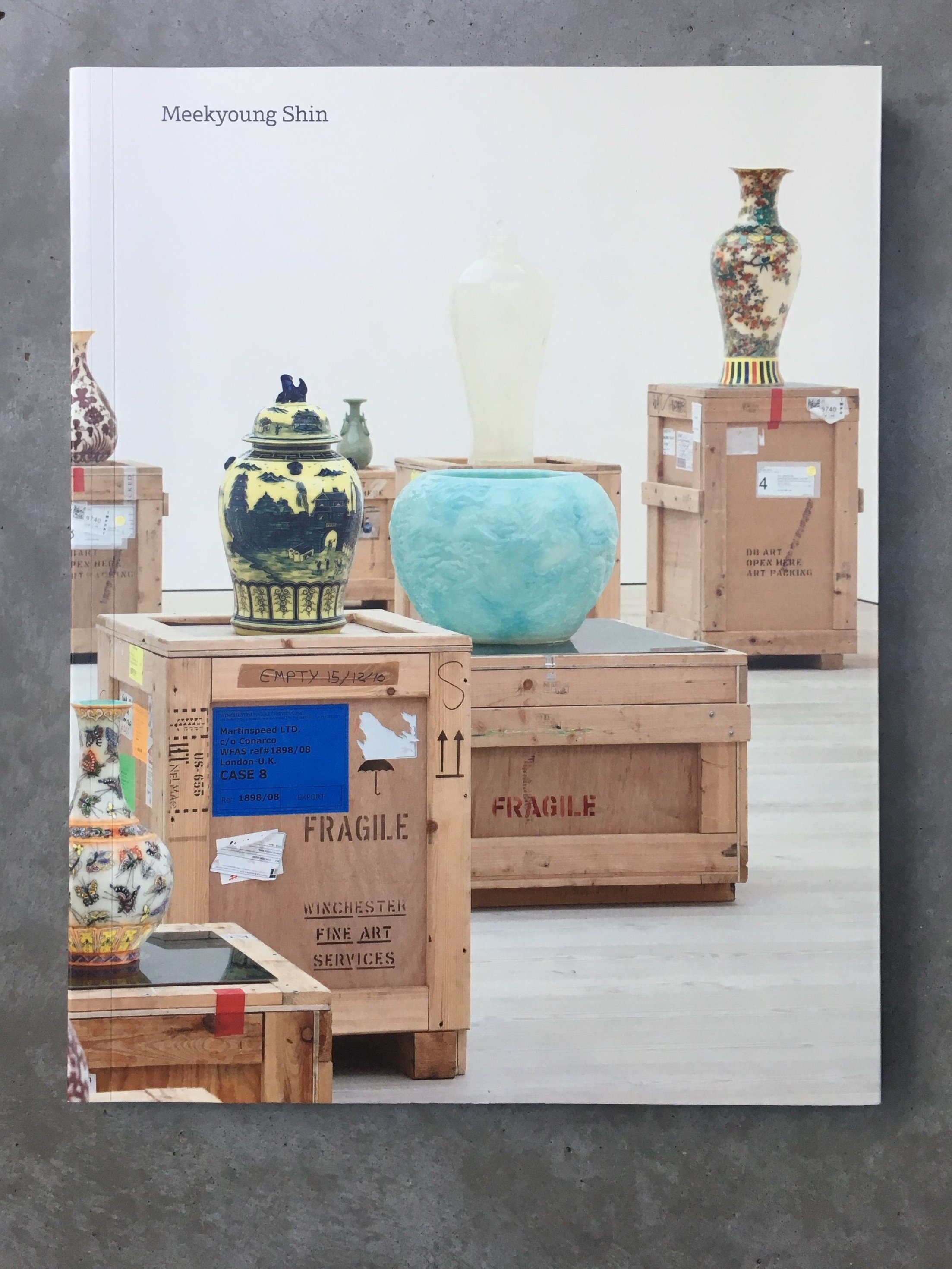

At the top of the stairs a wide landing gives on to the Senate Room, an ornate space with coloured plaster work and high windows looking out into the busy streets of Mayfair. Arriving in this space during Shin’s exhibition one would be forgiven for thinking that this was a gallery in mid-installation. A group of wooden packing cases, variously bearing labels denoting journeys across the globe, from exhibition venue to exhibition venue, were placed about the space. The crates had apparently been unpacked and on top of them, as if awaiting transference to their display cases, were positioned exquisite vessels from China. Yet closer inspection revealed these lustrous objects to be contemporary sculptures, brilliant examples of Shin’s careful craftsmanship.

To a western audience, these vases, based on Chinese porcelain made between the 16th and 20th centuries, are quintessentially Chinese. However, the artefacts they reference were actually created only for a European market and had little connection to the cultural life of ordinary people in China. The vases suggest several of the distinctive shifts which are central to Shin’s oeuvre. In addition to the cultural dislocation suggested above they embody a material one. For the substance they are made from, soap, also evokes instability. It is a material of erasure, subject also to being worn away through use. It is, quite literally, a slippery substance.

The first impression of Shin’s work is of astonishing technical facility and uncanny verisimilitude. Yet craft and illusionism in themselves cannot be enough to create meaning. What made Shin’s installation so compelling was the way in which it suggested a liminal status for the objects within it. They are not quite. Not quite what they seem. Not quite where they seem. They seem to be in transit or, in Shin’s preferred formulation, in ‘translation’.

Shin has described the process by which she makes the Translation Vase Series (1995 – present):

‘I began work on the collection when I moved to London from Korea in 1995. To create the works I make a silicon mould, pour in melted soap and wait for it to harden. I then carve out the inside and inlay the exterior with coloured soap or draw patterns using natural dye.’

She stresses however, that the work is about more than just material and craft:

‘It’s always interesting to see how people react to my work – they’re often amazed that they have been crafted so meticulously out of an unexpected material, but for me, it’s more important that they understand the meaning behind the work. It’s about two cultures colliding; I’m playing with the past and present, the opulent and the simple, East and West…’[1]

III

The second room in the exhibition was a smaller space, a room with an ornate ceiling and a set of beautiful glass-fronted wooden bookshelves along one wall. The cabinet housed Shin’s Translation - Toilet Series (2004 – present). In this work cast soap Buddhas were placed in museum toilets and gradually eroded as visitors used them to clean their hands. As a result the figures looked immensely old and worn, ancient and venerable. Here Shin’s process produces an effect of compressed time.

In a central position in the room, before the high window, Shin placed a large figurative piece, Crouching Aphrodite (2002). This astonishing work appears to be a fragment of ancient sculpture, carved from marble. However, close inspection reveals several uncanny facts. The first, that the figure is in fact modeled in white soap, creating an extraordinarily convincing mimicry of stone. Secondly, that the figure bears Asian features. Rather than a piece of ancient Greek or Roman statuary this is in fact a self-portrait of the artist, adopting the pose of the famous Venus of Vienne now in the Louvre. Shin made this work in Seoul, basing it on a photograph in a book on classical Greek art published by Oxford University Press. She cast her own body in the same pose and then modelled the sculpture from the cast.

As an artist moving often between London and Seoul, cultural slippage – the production of ambiguity of meaning as a result of translation from one culture to another - is an everyday experience for Shin. She was first inspired to explore this in her art when she saw the controversial Parthenon frieze in the British Museum while studying at the Slade School of Art in the early 1990s. In basing her version of this particular classical piece on her own body and face, Shin enacts an unnerving piece of hybridity. Put another way, the work is clearly not quite right - being neither fully Asian nor fully Roman it inhabits a cultural limbo state.

In addition, Crouching Aphrodite announces an important theme within Shin’s work, that of doubles and doubling. The version of the Venus of Vienne in the Louvre is itself a double, a Roman copy of the Greek original. Shin’s works are not simply replicas or reproductions but strange twins, uncanny avatars of their precursors. And they are original works in their own right.

IV

The largest room of the exhibition held an astonishing spectacle, an expansive installation of more than two hundred vessels from Shin’s Translation: Ghost Series(2007-ongoing).

Throughout the very large space, a series of raised platforms held groupings of translucent glass vessels, arranged according to colour. The effect was of a series of glowing pools of intense colour, a chromatic infusion. Carefully lit from above, and with the room itself in low light, the vessels glowed like precious stones or stained glass. Some were very large, others small, some short and round, some tall and elongated, with delicate extended necks. The vessels themselves gave the impression of incredible fragility and of great age. The air was suffused with perfume.

Shin calls these vases ‘ghosts’ and there is indeed something ghostly and mysterious about them. They emerge from the shadows like apparitions. Unlike the Translation Vase series they are mostly free from surface decoration, as if unfinished or somehow reduced to their essential form. The combined effect of placing so many together is of an array of typologies. Yet the only guiding principle in this disrupted taxonomy is chromatic.

What is a ghost? It is generally understood to be a being or creature held in limbo, perhaps trapped between two worlds (here and thereafter). Equally, a ghost is a remnant, an immaterial presence as a reminder of something now absent. The ghost is an insubstantial echo of a former state. It is something in transition. Soap might therefore, being a seemingly so transient and unstable material, be the ideal substance from which to materialize a ghost.

V

In the final room of the exhibition, another very large space, Shin showed a group of life-size statues. The first, in a space of its own, was Translation – L’Innocenza Perduta, 1862 by Emilio Santarelli (1801-1886), (1998, restored 2009), a large piece depicting a draped seated female nude, atop a large marble plinth. Beyond this, on a long raised plinth Shin presented a series of kouros figures in varying degrees of polychromy, Translation – Kuros (2009).

This final space was the one in the exhibition that most closely adhered to the appearance of a conventional museum display of antiquities; with plinths, spotlights and so on. Thereby demonstrating a further semantic shift within Shin’s work, a playing with the conventions of museological display and the aesthetic expectations created by the context of the contemporary art gallery. As elsewhere in the exhibition, the aroma of perfume was powerfully present, serving as another way of undermining the verisimilitude of Shin’s copies and reminding us of their material reality.

Her immaculate technique is both the point and not the point. If her versions were crude and unconvincing they would be rooted too deeply in their present tense, the time and place of their making. The accuracy of her renditions opens up the semantic gap into which the work slips, the shifting territory of translation. They are both close, and not close enough.

It is a convention to say that something will always be lost in translation. But might this be in error? Might something also be gained, something that was not there before? Salman Rushdie has suggested exactly this:

‘The word 'translation' comes, etymologically, from the Latin for 'bearing across'. Having been borne across the world, we are translated men. It is normally supposed that something always gets lost in translation; I cling, obstinately to the notion that something can also be gained.’ [2]

In Meekyoung Shin’s work the notion of translation is a double-sided lens that clarifies meaning in two directions. Translation equals transformation. Shin’s copies cast new light on the meaning of their originals. Conversely, the originals cast light on the copies. They are doubled. Yet Shin’s versions are fragile in a way that the stone and clay originals are not, subject to the ability of water to dissolve and erase. Their fragility – their tenuousness – is part of their meaning.

In 1943, writing of Henley's translation of Beckford's Vathek, Jorge Luis Borges commented (approvingly) that ‘the original is unfaithful to the translation…’[3] It is a fascinating (and typically Borgesian) inversion of the usual cliché and as such gives us some sense of the way that original and translation are locked in a two-way discourse. This is a notion that Shin’s work embraces.

It is through this discourse that Meekyoung Shin’s work bears witness to one of the overriding determinants of cultural life not only in the twenty-first century but of the last five hundred years, that of cultural dislocation. 6 Burlington Gardens, with all of its ghosts, the echoes of past exhibitions, its history of intellectual enquiry, museological innovation and its present use as a platform for contemporary art, provided Shin with the perfect context to extend her exploration of these very important ideas.