painting facts: The art of karl weschke

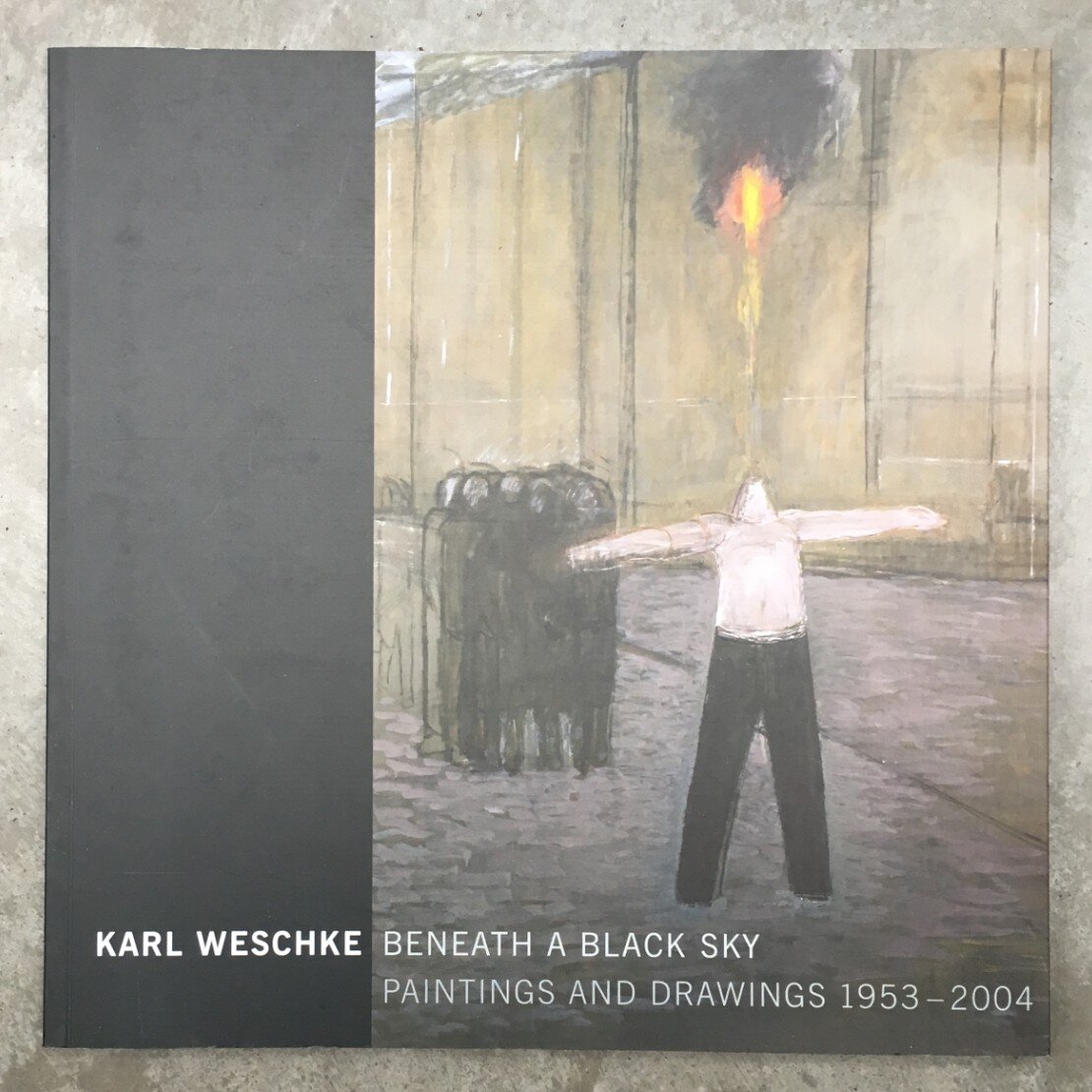

Karl Weschke: Beneath A Black Sky: Paintings and Drawings 1953 – 2004 (ed.), exh cat., Tate St Ives, 2004

In the summer of 1977 Karl Weschke had a diving accident off Priest Cove at Cape Cornwall, making an emergency ascent to the surface of the sea from 150 feet down. It was a hot summer’s day and when they reached the shore his companions lay him out on the beach to recover, exhausted and in pain. In his black diving suit the heat of the sun was unbearable, and Weschke found that he was barely able to move and unable to stand. He felt, he later said, like ‘flotsam’.[1]

Subsequently, Weschke painted two pictures: Body on the Beach 1977 and Caliban 1978. Both depict a figure lying on the foreshore and, although similar, they are also very different. In Body on the Beach the figure is inert, lifeless, ‘a piece of meat’[2]; it becomes a part of the landscape that surrounds it. In Caliban the figure is raw, clawing its way back from the brink, struggling to stand. Both works are, in a sense, exemplars of Weschke’s principal themes: a significant, perhaps traumatic, incident or encounter and its aftermath; the human body under duress; a struggle; the landscape. Each relates directly to the diving accident.

Weschke began Body on the Beach first. It is a relatively straightforward depiction of his situation after the accident – ‘a person in the ultimate situation of distress’ – although crucially the imagery has been purged of detail thus rendering it general, universalised.[3] As he worked on the painting Weschke listened to a production of The Tempest on the World Service and a parallel between his experience on the beach and the action of the play was suggested to him. Weschke recalled a scene from a film of the play in which the actor playing Caliban, Prospero’s ‘thing of darkness’, struggles to stand, assailed by magic and weighed down by skeins of seaweed.[4] He began to work on Caliban alongside the first painting; each image articulating some different aspect of his experience on the beach. The second painting moves further from the original incident. It dramatizes a human dilemma – the struggle for survival – but also evokes Prospero’s threats of ‘dry convulsions’ and ‘ages cramps’ and his warning to Caliban that ‘…tonight thou shalt have cramps,/Side stitches that shall pen thy breath up.’[5]

That the diving accident was the inspiration of these two paintings serves to confirm a fundamental characteristic of Weschke’s art, that it is rooted in actual experience. Weschke’s paintings – landscapes, depictions of the human body, mythical subjects – articulate great simple truths. Yet what we see in these paintings are the facts of his life – personal, individual moments of experience – translated into images of universal significance. Weschke’s art is an extraordinary re-imagining of the facts so that, as Weschke has said, ‘the painting itself becomes a new reality.’[6]

---

Weschke began to make art towards the end of the 1940s. During the war he had trained as an air gunner with the Luftwaffe before fighting with a commando unit in Holland and being captured, shell-shocked and exhausted, and hospitalised. After the war he interned as a POW in various camps around the UK. For a long time he resisted attempts at ‘re-education’ but later, at Radwinter near Saffron Walden, he attended History of Art lectures (learning for the first time about German art). At Wilton Park he was befriended by Tom Driberg who took him to see exhibitions, including Van Gogh at the Tate Gallery in 1947. He had begun to make carvings and drawings in the camps and when, in the following year, he was civilianised he resolved to stay in England, hoping to become a sculptor.[7]

Over the next five years he lived in London, Scotland, Spain and Sweden. He studied sculpture at St. Martin’s School of Art in London for a term, the only formal art education he has received. His work from this time is tentative, experimental. He drew a great deal and gradually his attention turned to painting. He made work in a range of modernist styles, most notably Expressionism, as can be seen from the earliest painting in the present exhibition. Portrait of Lore No.2 1954 is notable for the way it anticipates a number of characteristics that have been constant throughout Weschke’s career: volume is emphasised and specifics are minimised to create an image of monumentality and universality. The palette is limited, colour deployed tonally. It is interesting to note that despite this, Weschke considers the painting a good likeness of the sitter.

In 1953 Weschke met the painter Bryan Wynter and in 1955 Wynter helped him to find two cottages at Higher Tregerthen, near Zennor. He went to Cornwall mainly, he said, ‘because it was cheap.’ The cottages had once been used by Katherine Mansfield, DH Lawrence and John Middleton Murray and Weschke used one to live in and one to work in. The move to Cornwall represented a turning point: ‘I used the Mansfield cottage to start my life as a person down here, and the Lawrence cottage to start my life as a painter.’[8]

From 1955 onwards, emboldened by friendships with established artists such as Wynter, Roger Hilton and Peter Lanyon and with the poet WS Graham, he began to make work which bore the stamp of his individual artistic personality; dense, powerful paintings that seemed, to one contemporary critic, to evoke the ‘fears and sorrows of our civilisation.’[9] His work at this time was dominated by landscape (characteristically given generic titles such as Red Landscape or Immediate Landscape rather than identified as specific locations) but in a number of paintings, such as Blue Horse 1957 and The Apocalypse 1957-8, ominous, symbolic figures of riders and horses also appear, anticipating later works. In his reclining figures, connections to landscapes are suggested. Paint is applied in heavy impasto, sometimes with a palette knife, sometimes scored to give texture. Colours are muted or dark. The mood is oppressive, melancholy. These works come the closest to abstraction of any of Weschke. They were, he said, ‘landscapes by implication.’[10] In them the influence of Weschke’s Cornish contemporaries, particularly Lanyon, is evident, although it was David Bomberg who Weschke was most consistently compared to at the time.

In 1958 Weschke’s first solo show was held at the New Vision Centre, London. The exhibition attracted the attention of John Berger, who went on to write about his work on three separate occasions in the next two years. Berger praised the way that Weschke’s paintings ‘vividly convey the weight and “settlement” of his landscape forms’.[11] He also discussed what he perceived as Weschke’s ‘passionate identification’ with his subject matter. Berger’s notion of ‘identification’ offers a more useful framework for understanding Weschke’s work than Expressionism, the much contested historic term that is most frequently attached to his work.[12] For, while there are some superficial resemblances between his work and that of earlier German artists Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Max Beckmann, Weschke’s work is not primarily concerned with the expression of interior states, or of heightened emotion. Rather he is interested in creating images which will provoke a sense of recognition; in both artist and spectator. His engagement with the subject goes beyond physical appearance; the narratives implicit in his canvasses arise from personal experience; his landscapes from the experience of being in the landscape, as opposed to looking at it. Each painting is therefore an invitation to experience this creative engagement, this ‘identification’ with the thing represented.[13]

---

In 1960 Weschke moved to a small cottage at Cape Cornwall where he has lived ever since. It is remote, set in a harsh and unwelcoming landscape; with the desolation of the moors on one side and the vastness of the Atlantic on the other. It is a place that recurs again and again in Weschke’s work. The cliffs and coves below his home are the setting for Floating Figure 1974 and The Pool 1966; the view across the valley from his home to the ancient hill of Kenidjack appears frequently and is the setting for images such as Figure in a Landscape 1972 and Feeding Dog 1976-7. Here Weschke found isolation, and close proximity to nature; a vantage point. It is a place that has undoubtedly influenced his work, specifically its toughness, its austerity. The self-imposed isolation of Cape Cornwall has also reinforced Weschke’s self-identification as an outsider – both as artist and person – an exile.

Following the move his work began to change. He started to work on a larger scale, to use washes of paint and line, having come to regard the use of thick impasto as ‘false acts of bravura’.[14] This enabled him to construct his images through a subtle process of accretion. Although the final image in Weschke’s paintings often seems almost perfunctory it is actually the end result of a long process of trial and error, advances and returns, which bear comparison with the working methods of his near contemporaries Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach as well as older artists such as William Coldstream and Alberto Giacometti; a persistent remaking of the image, a kind of accrual of evidence.

Landscape has remained one of Weschke’s principal themes and in the early 1960’s he began to develop his characteristic treatment of it, in which it is approached not as a topographic subject but as a dynamic space. Such dynamism is suggested by the title and imagery of Meeting Point of Land and Sky II 1961, in which land and air are given equal weight and are animated by a powerful sense of movement. The landscape is also a space in which significant events might occur. This while Pillar of Smoke 1964 is ostensibly a depiction of gorse being burnt on the moors above Zennor it actually evokes a range of possible associations. The dark black cloud is vaguely anthropomorphic and certainly threatening, and consequently the painting can be read as a depiction of the aftermath of violence. It is a reimagining; the experience of the gorse burning has been augmented with Weschke’s memories of the Western front during the Second World War and an awareness of more recent events in Korea and Vietnam. An event in the Cornish landscape that comes to symbolise, through echoes and illusions, the ravaging of the landscape in conflict, and correspondingly carries human implications.

Weschke has also focused on the powerful natural forces that activate the landscape, which shape it and which can render any human presence within it utterly insignificant. From his vantage point high above the cliffs such forces are powerfully present, embodied by the great storms that role in off the Atlantic and which are depicted in paintings such as Sturmflöten 1965-6, Cloud over Kenidjack 1972-3 or Sturmauge - Gale 1974. Weschke has said that in such paintings he was trying to create ‘a visible equivalent for natural forces.’[15]

Thus Sturmflöten evokes a storm breaking over the cliffs by ascribing the forms of drums to cloud formations, and suggesting the pounding of tom-toms through lines of force. Such imagery was suggested not only by the visual and aural experience of the storm but by ‘a wind God blowing in an engraved vignette at the bottom of a map showing exploration roots in the Arctic.’[16] Cloud over Kenidjack heralds the imminent breaking of an ‘apocalyptic’ thunderstorm, while Gale echoes Turner’s use of the vortex in paintings such a Snowstorm – Steamboat off a Harbour Mouth 1842 which Weschke had admired on visits to the Tate gallery. Such paintings demonstrate an interest in the sublime which reaches its apogee in Weschke’s extraordinary depiction of The Gordale Scar 1987-8 directly inspired by James Ward’s vast painting of the subject, also in the Tate Collection.

Contrasted with such works are the paintings of the sea, which are often presented as ambiguous, both threatening and sensual. It is not clear, in paintings such as Floating Figure 1974 and Body in the Atlantic Sea 1982-4, whether the figures are drifting peacefully in a comforting and beneficial medium, or if they are in difficulty. Body in the Atlantic Sea was inspired by a radio report of a man overboard 200 miles out at sea off Cape Cornwall, yet the sea is calm, the atmosphere of the painting strangely peaceful. It has the peculiar quality of a dream.

This sense of contradiction, of tension between image and meaning, is typical of Weschke’s work. The sea represents ‘amniotic fluid, the very range of life’, yet is also ‘a powerful ruthless destroyer... an abstract uncaring brute.’ It is, above all else however, ‘a constant reminder of life.’[17]

---

Weschke’s Landscapes are bleak places and any human presence within them is necessarily marginal. Yet Weschke has often sited the human figure within such spaces. Paintings such as Figure in a Landscape or Caliban convey a powerful sense of isolation, the subject seemingly engaged in individual and abstract struggles. The solitary presence – figure, animal, tree – with which the audience is invited to identify, is the recurring motif in Weschke work and suggests an affinity with Existentialism.[18]

Where people come together in Weschke’s paintings, some threat or trauma is often implied. In The Meeting 1974 a naked figure is threatened (or comforted?) by a second figure on horseback. In The Fire-eater with Spectators 1984-6, which is derived from the experience of watching a street performer in Frankfurt, the pose of the figure recalls a crucifixion, while the crowds of spectators seem to huddled together in fear.[19] Such scenarios present human beings as vulnerable, frequently distressed, and above all alienated. They reflect the world formed in the aftermath of the War, and connect with prevailing debates from the late 1940s and 50s concerning the breakdown of the established order, and an increasing emphasis on individual consciousness and responsibility. They articulate a mood of intense disquiet; these are images in which the memory of war, intimations of Cold War anxiety, economic privation, the experience of alienation and exile are reconfigured as intimate and specific scenarios of universal significance, as archetypes.

Within Weschke’s work images of consolation are rare but important; they appear most powerfully in his large triptych Study for the Woman of Berlin 1969-70. In this large painting naked women comfort and console one another in the aftermath of a rape, which is depicted (or alluded to) in the left-hand panel. This and other works have earned Weschke accusations of voyeurism, and of depicting sexual aggression and violence as compelling and erotic. Yet Weschke real motivation for depicting such scenarios is sympathy. He has said ‘Bacon paints violence. I paint the violated.’[20] He has written approvingly of Goya, who ‘through the power of his work conveys so much compassion for his persecuted, abused and violated fellow humans that it amounts to an indictment of the perpetrators of these acts of violation.’[21] In such images Weschke does not celebrate the aggressor but empathises with the victim. Yet he also recognises that such situations are rarely black-and-white. His vision is ambiguous; hence the frequent blurring of status between aggressor and protector in his paintings, a theme which is particularly pronounced in the works featuring dogs, such as Feeding Dog and Fighting Dogs 1978. These extraordinary images are neither anthropomorphised nor sentimentalised. Each animal’s behaviour is true to its nature, the result of Weschke’s close observation of his Borzoi hound Dancov. As with so many of Weschke’s figure paintings they bear witness to the struggle for survival.

---

In 1990 Weschke fulfilled a long held ambition to travel to Egypt, visiting important sites in the Valley of the Kings along the Nile, sketching compulsively everywhere he went. He returned again in 1992, 1997 and 2000, and these visits have had a powerful effect on his work. Most noticeably is the change in his pallet. As Weschke said ‘The light did affect me, the blue was lapis-lazuli, the yellow was ochre, the colours were substances.’[22] Such substances permeate his recent canvasses.

Yet while Weschke’s subject matter would also appear to have been transformed by his Egyptian experiences these paintings can be seen as synthesis and continuation of his pre-eminent themes: humanity and landscape. Here we see how man has attempted to impress himself upon the land. Here we see how time ravages his monuments. Vast temple structures are overwhelmed and subsumed by the immenseness of the desert. In many works lone palm trees (often buffeted by desert winds) or stone columns fulfil the same role as the isolated figures in Weschke’s other work. Despite the size and antiquity of the places depicted they are empty; unpeopled. In The Nile near Kom Ombo 1994 the evidence of human agency is reduced to a few faint charcoal marks laid across the painted landscape.

---

For Weschke life is to be celebrated. But for this process ‘honesty is a prerequisite.’ The landscape is not necessarily pretty or welcoming, it can be dense, ugly, threatening, it can inspire fear. The same is true for the human body. Human beings perpetrate terrible acts of violence against one another. Man is overwhelmed by his surrounding and his individual circumstances. Caliban’s struggle is not only one of survival, but also an attempt to better himself. Weschke’s paintings reflect all of this. His work is raw experience re- made into a new reality; a response to, a challenge to, what he calls ‘the night fears, the survival fears’.

Personal honesty is also important: ‘The painting also utters the existence of the painter, because the painter displays himself, always.’[23] Weschke’s work, which now spans more than fifty years, is an extraordinary assertion of life, and of his life in particular.

[1] Unless otherwise stated all quotes are taken from conversations with the author, September 2003

[2] Quoted in Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1980-82, Tate Gallery, pp.219

[3] ibid.

[4] William Shakespeare The Tempest V.1.275

[5] The Tempest 1.2.325-6

[6] ‘Talking about my painting’ in Karl Weschke, exhibition broadsheet, Tate St Ives 1995

[7] A detailed account of Weschke’s life is given in Jeremy Lewison Karl Weschke: Portrait of a Painter, Penzance 1998

[8] Quoted in ‘Painter of Life’ What’s On Inside Cornwall Feb/Mar 1995

[9] MW, ‘Artists must not neglect masses – Educationalist’ in St Ives Times 16 Dec 1955

[10] Quoted in Michael Strauss ‘Karl Weschke’ in Burlington Magazine Dec 1960

[11] John Berger ‘Three Landscapes’ in New Statesman 17 May 1958

[12] In an earlier review Berger himself had categorized Weschke’s work in this way, writing of ‘the discipline behind his marvelling and Exressionism’ New Statesman 10 May 1958

[13] Frank Auerbach has also spoken of ‘identification’: ‘Paint is at its most eloquent when it is a by-product of some corporeal, spatial, developing imaginative concept, a creative identification with the subject.

[14] Quoted in Lewison p.26

[15] Quote in Bryn Richards, ‘Weschke at the Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol’, Guardian 20 April 1968

[16] Karl Weschke, exhibition catalogue, Plymouth Art Gallery 1971

[17] Quoted in ‘Painter of Life’ 1966

[18] Weschke was certainly familiar with Existentialism from the 1950’s onwards, having engaged in discussions with members of the Borough Group on the subject. He read Kierkgaard, Camus, Sarte and Gide

[19] Weschke’s use of religious imagery, which occurs in just a few key works from the 1950s, for example in the huge deposition Triptych 1958-9 (Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney) and related works from the early 1960s such as Hanging 1961, also connects to such contemporary concerns and work by artists such as Picasso and Bacon. Weschke’s use of imagery is close to Bacon’s, who described the crucifixion as ‘marvellous armature in which to hang all kinds of thoughts and feelings’ (Quoted in Michael Peppiat Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, London 1996 p.99)

[20] Quoted in John Russell Taylor ‘Compassion firmly in check’ in The Times 16 Sept 1981

[21] ‘Karl Weschke on Goya’s Third of May 1808’ in The Guardian 18 June 1996

[22] Quoted in Andrew Lambirth ‘Karl Weschke’ What’s On in London 10-17 July 1996

[23] Quoted in Giles Auty ‘Autumn Fires’, The Spectator 23 Sept 1989 pp.45-46