Stupid Like A Painter: A Correspondence between Pascal Danz and Ben Tufnell

Pascal Danz: blank out Exhibition Catalogue Zurich: Haunch of Venison 2009

Duchamp rejected 'retinal' art in favour of art made 'in the service of the mind'. He used the old French insult, 'stupid like a painter' to ridicule the artist who paints only what he sees in front of him. What does it mean to be a painter in the post-Duchamp, post-Conceptual world, at the beginning of the twenty-first century? Is this not an anachronistic practice?

Just because painting is the oldest medium doesn't mean that it has to be anachronistic. In any case I am a romantic and anachronism has something anarchic about it because the concept of time is removed and a certain fool's freedom is guaranteed...

Of course, after all the small and large declarations of its death, painting is still one of the most interesting and one of the very least exhausted media and will remain so. The crises after the emergence of photography, after Duchamp, after the new media in the 80s and 90s emancipated painting through self-reflection, redefinition and sometimes self-justification. Like every other medium, painting has qualities and characteristics that cannot be replaced by anything else and therefore allow a unique investigation of perception. The physical and sensual presence of a painted image is simply quite different to that of a video or a photograph.

Your work in fact presents a close engagement with photography. In this sense you paint what you see in front of you, albeit in the highly mediated form of photographs, newspaper images, snapshots, jpegs and so on.

Photography or an image similar to a photograph is the determining factor as the basis of my painting. But I want to say quite pragmatically that for me personally it makes very little difference whether I see an image as a photograph, film or theatre or as a real landscape. These images have one thing in common: they have been neither made nor selected by me. By this I mean that with all these mediated images I receive a selection made by someone else, a second or third pair of eyes belonging to another person who sees (for me). Someone else has decided that something should become an image. In addition, the vehicle for the image, whether newspaper, digital image, analogue photograph, film etc. plays a critical role regarding my own reception. My interest in the image made by someone else lies in the distance between the object, the image, the illustration and the vehicle, right up to the irritation it provokes in me.

What is noticeable is that in my collection of images almost every single one includes some kind of disturbance, whether technical (like bad printing, dust, over-exposure), formal or thematic.

Whether I paint what I see in front of me? I think it's more correct to say that I try to paint what I can't see, the gap between the depicted and the thought. To visualise what the other set of eyes has not seen or not taken notice of.

Can you explain more about this notion of 'disturbance' in the images you are drawn to, and also the 'irritation', which you find interesting. I'm very curious about this, especially as you have also talked about the necessity of 'seduction' in the past. These seem like contradictory impulses. Is there a push-pull you are seeking?

This push-pull is an important aspect of my work on various levels. What interests me concerning the irritations in my work is this to-and-fro between personal and objective perception, insofar as perception can be objective at all.

Mistakes in images don't exist since it's not possible for an image to be wrong. Images just are. It's only in the reception that images are judged. The personal, that which can't really be objectified, is part of this. And it's exactly this personal element for me that is decisive in the first phase of the formation of an image. I can be attracted to an image in many possible ways: through seduction, through ugliness, awkwardness, through colour, form, content but also through errors or what is missing, through how it communicates time...the list can go on endlessly. I want to allow all these initial impressions to take their effect on me unfiltered so that I can follow my own, undistorted, spontaneous process of seeing. So images that at this first stage say something to me get put into a large box. They lie there for a while. Put metaphorically, the box can also be described as my memory.

The second part of the process is about looking a second time at the images. By this I mean that after a period of time the sedimented images are rummaged through again and examined with a new gaze. Checked for the irritation that was obvious the first time. Various layers of the images' importance or their urgency are formed through this process of looking over and over again. Those floating at the top are the ones that haunt me in terms of their irritation. Other images, however, disappear completely because after the second viewing the fascination or irritation has dissolved into nothing and everything has become explainable.

And now the really exciting part of the work begins. It's about creating the path from the personal perception to an objective experience. By this I mean the route from the initial private attraction to the possibility of an image that has to move beyond what I experience personally and creates the probability of irritating or seducing other viewers. But when I talk here about seduction I mean this rather in the sense of the push-pull you mention above. The gaze should be seduced so as to be directed to the place of the ‘strangeness’. It's a push and pull between the familiar and the unknown, the open place. I often name this with a black or white hole – the place where the gaze loses itself (or is led) and must repeatedly return to. With my work then I want to communicate neither a thematic nor a formal sense of security, but to create rather through the provocation or seduction the basis for a reflection on seeing.

This ‘push-pull’ is therefore a means to question the gaze, the habit of seeing and the allegedly familiar and to formulate it anew or differently.

When I before commented on disturbance and irritation, this is also in the sense of an abstract idea of amnesia: an image is visible, without, however, being able to create an immediate sense of security through the possibility of being named. As the first glance of something that does not yet have a name and is not yet inscribed in a history of experience. Seen in this way, my paintings are not solutions or answers but much more just possibilities. In this way they are perhaps also documents of failure.

How do the works on paper sit in relation to the paintings? Are they preparatory works, part of the process of sedimentation of images that you've mentioned, or are they completely independent?

For a long time the works on paper were of a purely supportive nature, that is, as you mentioned above, the first spontaneous field of experimentation between sedimented images and manifestations. For a long time I didn't really take these works seriously and rarely gave them a second glance. It's only in the last few years that the status of the works on paper has changed for me and I've allowed them a certain autonomy. I'd describe them as independent. Or at least as a chrysalis stage, that is as something in the metamorphosis from idea to painting.

I don't want here to confuse the term 'works on paper' with 'drawings'. Drawing has something chirurgical for me, it is an operational intervention into a support: through one line the surface is split just as skin is cut open by a scalpel. And my works on paper are distinguished from such drawings by the fact that they have a strong painterly character.

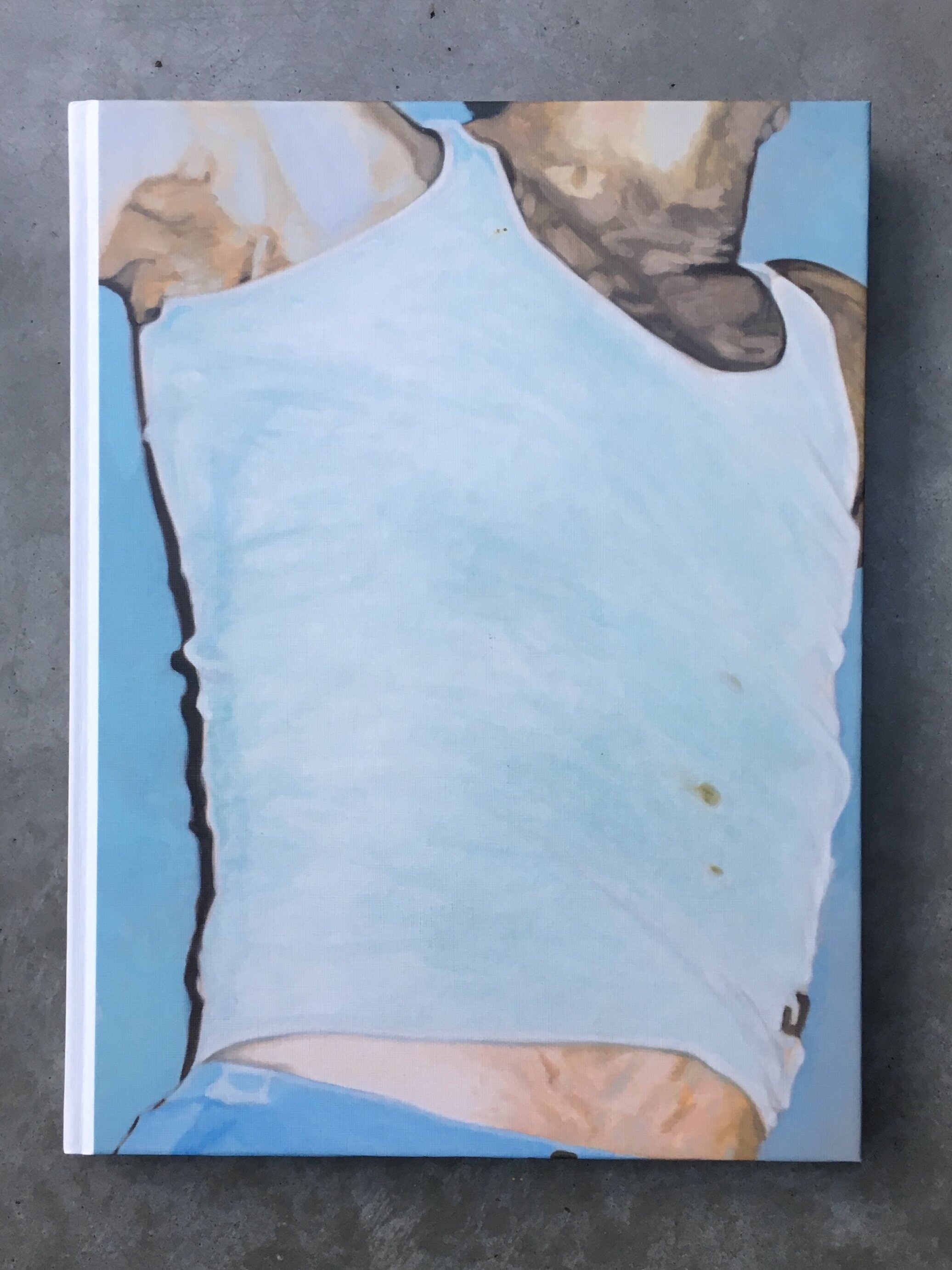

It’s clear that ideas of absence, of erasure, are very important to you. Could you talk a little bit more about this idea of the black/white hole - the 'place where the gaze (blick) loses itself' - in relation to your recent work? I'm thinking in particular about the series of torsos, where the white vests both model form and yet also offer a kind of blank zone. And also the new mountain landscapes where there is often a passage where the image is lost in a swirl of fog or cloud, and again there is an absence.

Are you drawn to images where this void (lücke) occurs naturally, or is it something that you insert into the painting (or rather where you extract the image information in order to create an absence)?

Of course the aspect of the ‘white’ and ‘black’ holes in the works mentioned above is applicable – even if this is almost too direct. Concerning the ‘torsi’ you mention (1972 (body), 2007 and 2007 (body), 2007), these are one part of a group of works on a theme that I return to repeatedly: the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. Or more exactly, the hostage-taking by the Palestinian group Black September that took place there and the resulting media spectacle that had never been seen to this extent before. For an eleven-year old boy, as I was then, it was not really a comprehensible event. But nonetheless it left a deep visual impression: the terrorist in a balaclava on the balcony; the police on the roofs, in sports gear and carrying guns; the crowds of spectators... This group of paintings refers to the only victim that died at the hands of the hostage-takers: an Israeli wrestler. He was discovered shot dead in the flat of the Israeli Olympic team. I was fascinated by the sports shirt in the photographs of the scene, turned almost white by the flashlight, that clothed the dead body – like an empty projection surface that in the intensification of the flashlight more or less obscures the body as a volume. I've tried to recreate in the painting this absence of body and the idea of the projection surface to be filled by the observer: the nothingness, the empty space, the place of amnesia, the being thrown back onto oneself, exposure, no avoiding anything... The canvas practically only consists of the almost monochrome surface of the shirt and the gaze is directed more and more from the hints of a body at the edge of the painting towards the centre, ending there in the lack of information, in one's own exposure, as it were. If the gap is filled at all, then, by the observer, the observers are ‘activated’. All possible information on the canvas is pushed to the edge and is legible only in fragments as well as being highly abstracted.

The figure is upright, so the weight of the body is therefore irritatingly wrong. The figure appears slightly like a dancer and also has something rather Christian about it: crucifixion, sacrifice. It thereby becomes a thing of belief. But also a thing of perception: everything either leads out of the image or remains in the centre. The dissolution of the body is also a reference to what painting is: two dimensional and without answer.

I wanted to contrast this one torso image with something, other bodies, without however making a connection with crime photographs and without having to express the sensation of real death. I found a way by taking up the position of the dead body by myself: in my painting clothes, photographed from a camera fixed to a tripod (the foreign eye), uncontrolled and flashed in the half light. Out of this photographic preparatory work developed, on the one hand, two large format paintings that expand the work described above. In addition and parallel to this grew a small-format study group of ten works that in contrast to the large paintings don't play with emptiness, as I included on these last ones the traces of paint on my clothes. It's interesting how these traces of paint suddenly lose their harmlessness and acquire the undertone of crime and the colour of the shirts is read differently – and at the same time becomes an image within an image. In contrast to the larger works where the empty canvas is thematically closer, with this small-format group the materiality of painting moves into the foreground.

Concerning the paintings of mountains that you talk about, the treatment is almost similar. The places lost in a swirl of fog, such as those that appear in wave, 2007 or mountain, 2007 but also in the hard, almost flat black surfaces in mountains, skinny, 2007 and stagey mountains, 2007, are on the one hand painted gaps (as information is avoided) but on the other hand also carriers of information (because that which is avoided also transports meaning). If the empty space in the torso was already predetermined by the source material, so in the landscapes the empty space is above all a constructed one. Just as the landscape in general is constructed, the painted structures are based in each case on various source images and are placed by me on the canvas like a collage, sampled and extended with invented areas.

It's important to me to always undermine the ‘familiar’, to unsettle and to question. These areas of non-information in the paintings should provoke questions about seeing and lead the viewer from a consumptive to a mentally active interventional seeing. By interventional I probably mean that the places lacking information, the holes that is, should show that that which is seen is also active, in an undefined way ‘looks back’. The large landscapes then are on the one hand layered stage sets - highly constructed artificial places – and on the other hand subliminal scenes of events or crimes. Crime scenes on the one hand through the absences in the image, but on the other hand through the palette too. An example would be the painting mountains, skinny, 2007. My starting point for the palette was tattoos, a faded black, such as occurs through the layers of skin over the embedded colour. This connection to the body is significant for the landscapes insofar as the mountain landscape itself refers to a ‘scene of the crime’ that is connected in a macabre way to the body. It concerns the scene of an aeroplane crash in the Chilean Andes, where some of those involved in the accident survived only because the dead people were eaten. I tried to show this borderline experience, this transgression of ethical taboos through the fragmented landscape, like a broken mirror. This image is a history painting without actors. The image itself becomes the actor, the active part.

Such paintings must also, of course, be able to function without advance information. For me it's not about confronting the viewer with exact details but much more about allowing a basic feeling for it to grow. The discomfort should provoke a second and third gaze.

I'd like to return to the notion of failure as I’m intrigued by your characterisation of your paintings as 'documents of failure'. I was struck also by a phrase you used in an interview a few years ago: "...painting is a site of permanent failure, a site of passage, a site of possibility without any absolutes." Can you explain a little more about this sense of failure? Does it actually suggest a perverse kind of freedom for you as an artist (the freedom to fail)?

As the images I produce do not present solutions but merely possibilities or suggestions, they are spaces of transit, provisional places. Nothing is secured or given. Seen in this way then, they are always only an approach towards what have been thoughts without really reaching them. This gap between idea/conception and realisation is possibly the place of failure. But only through taking failure into account can the unexpected emerge. The process of failure is necessary in order to keep the system around the question (instead of the answer) open.

In conclusion we can recall a quote from Samuel Beckett:

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter.

Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” (Worstward Ho,1983)

Finally, I thought you might be interested in something that the British painter Victor Pasmore said in 1962. He said "The vitality of representational art rests on the importance attached to subject matter. In an age of photography the subject matter that inspired the Impressionists and the Cubists has lost its impetus. It is only in a renewed interest in tragedy and comedy that representational art can develop...." What do you think? Does this still ring true?

I like this quote, not because I agree with it but because I read it as ironic. The ironist deals with how something and not what is being said, paying a distanced attention to the content of what is being said in order to identify gaps between knowledge and productive miscommunication. And this is more or less the idea at the heart of the old discussion between abstract and figurative art.

I’d like to juxtapose the quote above with another from Soren Kirkegaard:

“just as scientists claim that there is no true science without doubt, so it may be maintained with the same right that no genuinely human life is possible without irony” (Über den Begriff der Ironie. Mit ständiger Rücksicht auf Sokrates (Magisterdissertation 1841))